Long before the term globalization entered our daily language, thought-leaders such as Peter Drucker[1] predicted that this phenomenon would require corporations to take on a different attitude and skill set for success. In the mid-1970’s, Macrae (1976)[2] writing in The Economist, proposed that the people working in corporations should behave as if they were entrepreneurs, that is, in a manner that fostered creativity, innovation, risk-taking, competitiveness, and personal accountability.

Pinchot and Pinchot (1985)[3] coined the term intrapreneur to describe someone working with an entrepreneurial attitude in a corporate environment. By the early 1990’s, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language[4] added the term intrapreneur to its database, as “A person within a large corporation who takes direct responsibility for turning an idea into a profitable finished product through assertive risk-taking and innovation.”

Despite the great interest, it proved extremely difficult to implement. Studies of intrapreneurship focused on the same elements as those from the study of entrepreneurs. This perpetuated the notion of a single phenomenon spanning different contexts (De Jong & Wennekers, 2008)[5]. Kao, et al. (2002, p. 6)[6] described intrapreneurship as “A basically decent idea” that has encountered a number of challenges, most notably the unwillingness of corporate owners to share their equity with employees. In other words, taking ownership out of the picture may be like removing the engine from an automobile.

The members’ dining room at the Toronto Stock Exchange was crowded. I was having lunch with a client, the president of one of the world’s largest technology companies. Halfway through our main course the conversation drifted to one of my companion’s favorite topics: Employee motivation. “The idea that you can motivate someone to do anything they’re not already motivated for is a hoax“, I said. “All you can ever do is to provide an environment that either brings out their inherent motivation…or one that suppresses it.” He looked frustrated. Suddenly he slammed his fist on the table, exclaiming, “I just want people with some entrepreneurial spirit…is that too much to ask?” I stared at him for a moment, contemplating a reply. Then it came to me: “If they were truly entrepreneurial, why would they be working for you?” I asked.

As a result of this exchange, we organized a formal study of Intrapreneurship (IP) looking at organizations that had successfully managed to implement it. The results were published in 2015[7]. The findings were both surprising and encouraging.

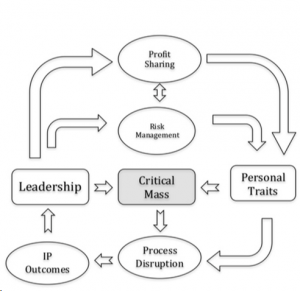

An interactive model of intrapreneurship is shown below. Note the pivotal role of a critical mass of intrapreneurial employees.

The study showed that intrapreneurship is a distinct phenomenon and that intrapreneurs are not “entrepreneurs-in-waiting”. It turns out that almost anyone can become an intrapreneur under the right circumstances. The single most important factor is Leadership’s consistent modeling of intrapreneurial behavior. This is also the reason few companies have been able to implement intrapreneurial cultures…so few corporate leaders know how to be intrapreneurs!

The success of intrapreneurship depends on building a critical mass of employees who are empowered to live intrapreneurial values, skills, and behaviors throughout the company. These capabilities are distinct and stable, although they share some commonalities with those of entrepreneurs, a factor which may well have led to the confusion between the two in the past research and literature.

Intrapreneurs are averse to personal financial risk and have only a modest expectation of profit sharing in recognition for their efforts. Leadership creates a context that enables and leverages intrapreneurial capabilities and motivation by mitigating personal risk and symbolically sharing some profit as a sign of recognition. Context and process interact through this critical mass of empowered employees to challenge and interrupt existing processes and to create new, innovative opportunities for shareholder value. This, in turn, produces the desired results that validate Leadership’s commitment to intrapreneurship.

By Steve Courmanopoulos, PhD (Psych)

Dr. Courmanopoulos is the Senior Partner and CEO of Medius International Inc, a global consulting firm providing expertise in three areas: Intelligence, Strategy, and Organizational Development. Click here for more information on the firm’s activities in Intrapreneurship, Company Culture, and Employee Engagement.

[1] Drucker, P. F. (1985). Innovation and entrepreneurship. New York: Harper Business.

[2] Macrae, G. (1976, December 25). The coming entrepreneurial revolution. The Economist.

[3] Pinchot, G. & Pinchot, E. (1985). Intrapreneuring. New York: Harper & Row.

[4] The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (1992). Intrapreneur. 4th Edition, New York: Houghton-Mifflin.

[5] De Jong, J., & Wennekers, S. (2008). Intrapreneurship: Conceptualizing entrepreneurial employee behavior. Netherlands: EIMbv.

[6] Kao, R. W., Kao, K. R., & Kao, R. R. (2002). Entrepreneurism: A Philosophy and A Sensible Alternative for the Market Economy. Hackensack, N.J: World Scientific Publishing Company.

[7] Courmanopoulos, S. (2015). The Dimensions Of A Successful Intrapreneurial Corporate Culture: A Grounded Theory Study. Private study. Medius International inc.